07/16/23

The history of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness is long and fascinating. There are many things we can learn from looking back on lives lived and decisions made. Today, I thought I’d delve into the history of the BWCA through the eyes of a geologist.

An Overview of What We Can Find

Minerals and rocks make up most of our world. We use rocks for construction, and use a myriad of minerals in our day-to-day lives. Copper wires help run electricity, halite, also known as salt, flavors our foods, and many places still use coal to heat homes. Many of the main categories of rocks are found in the BWCA, as well as the north shore of Lake Superior and much of the Midwest.

Igneous rocks such as basalt, rhyolite, and granite are found in large quantities here. There are two main categories of igneous rocks: mafic and felsic. Mafic rocks are high in iron and magnesium. These rocks tend to be darker colored. Think basalt. They are created by low-viscosity, or runny, lava that cools over a long period of time. Felsic rocks are higher in minerals like feldspar and silica. These rocks are lighter in color. Granite is a good example of a felsic rock. The lava that creates felsic rocks is usually thicker.

The main minerals that could be found in the BWCA are copper, nickel, gold, and iron. There are a number of abandoned mines in the wilderness before it was a protected area that used to hunt for gold and copper. There is one on the south shore of Jack Lake near the Baker Lake entry point, #39. This was a gold mine that shut down in the late 1800s.

Arguably the most well known rock to come from our area is the agate. These beautiful stones are made of microcrystalline silica, the same material that makes up quartz crystals. They formed in vesicles, or holes, in the basalt. Over millions of years, water saturated with silica would flow into these cavities and layer by layer the agate would form. Scientists still don’t understand the mechanism behind the creation of agates. It is a mystery that many are still trying to solve.

An Incomprehensive Geologic History of the BWCA (and north shore of Superior)

The oldest rocks that can be found in the wilderness area is a formation known as the Ely Greenstone. This Greenstone was created more than 2.7 billion years ago (bya). The rock was formed in a marine environment because at that time in earth’s history where we are now was under water. There are outcroppings on the southwest end of Moose Lake, the north shore of Knife Lake, and the east shore of Gabimichigami Lake. Between 2.7 and 2.5 bya, there were periods of intrusions into the greenstone by granite followed by deformation and erosion of the greenstone and granite followed by more granitic intrusions. The sedimentary rocks formed by the erosion are named the Knife Lake Group. These rocks can be found in Cache Bay of Saganaga, the south and northeast shores of Knife Lake, and Kekekabic Lake. After the second round of intrusions there was a long period of erosion. The Gunflint Iron Formation was formed around 2.0 bya. The main origin of this formation is thought to be an uplifting of the Knife Lake Group. The Gunflint Iron Formation is made up of sediment rich with iron. Best place to find outcroppings is the north shore of Gunflint Lake.

Approximately 1.1 billion years ago, the Laurentia craton started to split. This fault line runs from Oklahoma up to Thunder Bay, curves back down to run under what is now Lake Superior, and ends as far south as Tennessee or Alabama for a total of 1,800 miles in length. For some reason not yet known to geologists, the rifting stopped. If it had continued, there would be an ocean splitting the US in half! During this time of volcanic activity, lava that would cool into gabbro and basalt flowed onto the surface. It is in this basalt that the agates formed. By using seismic waves, geologists were able to get an understanding of how deep the layer of rock is. Roughly 15 miles thick in some places. The name for this formation is the Duluth Complex. You can find rocks around lakes south of the Kekekabic Trail. A couple modern day examples of rifting are the Mid-Atlantic Rift and Rift Valley in eastern Africa.

The last major event started between 3 to 1 million years ago. The Pleistocene Ice Age drew glaciers down from the north in many waves. Some of the most visual signs of the past glacial periods are striations. Striations are lines carved into the surface of a rock by the glaciers dragging other rocks over top. The last glacier receded around 10 to 11 thousand years ago. Once they were gone, the basins left behind filled with water to create the beautiful lakes we know now.

The Laurentian Divide

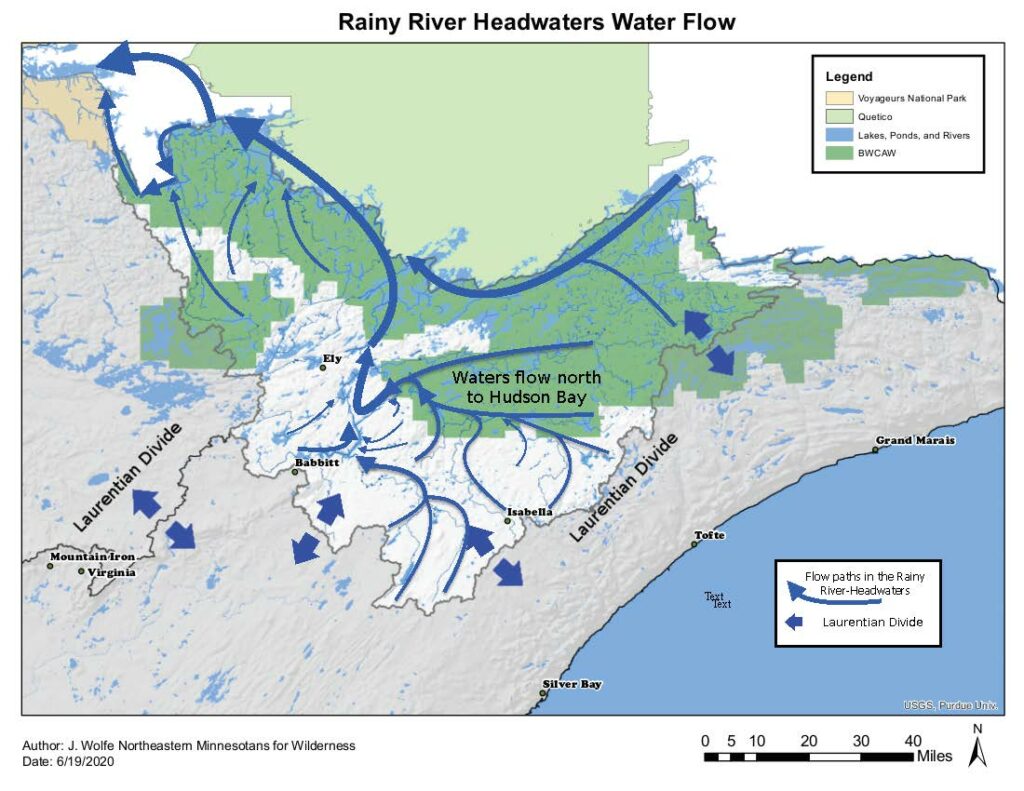

The Laurentian Divide runs through the BWCA near us at Sawbill! It crosses the portage into Beth Lake from Alton Lake to the west of us, and again north of us by Cherokee Lake. Waterways to the north of the Divide drain into the Hudson Bay and water to the south will end up emptying into the St. Lawrence Seaway.

To conclude

We can learn a lot from the rocks around us. There’s a saying in the geology world, “ The present is the key to the past”. By studying the rock formations and the processes that act on them, we can slowly uncover how the Earth came to be. The BWCA is a unique place that has many windows to the past sitting in plain sight. All we need to do is look.

Sawyer

Author’s note: If anyone is interested in learning more, I recommend a short pdf called, “It’s Written in the Rocks” by Dr. Paul W Weiblen and “Roadside Geology of Minnesota” by Richard W. Ojakangas.